Introduction

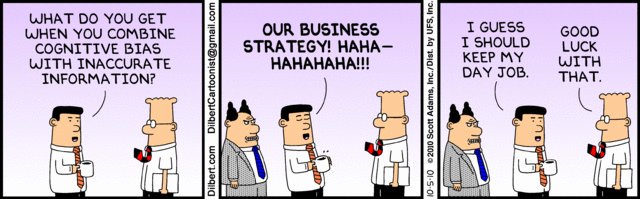

In the early 70’s, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman introduced the world to the idea of cognitive biases:

A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, where individuals create their own “subjective social reality” from their perception of the input. Cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, or what is broadly called irrationality.

See Cognitive Bias, Wikipedia.

In todays post, I’m going to look at five cognitive biases that regularly affect product design, and present a strategy to avoid them:

- The above average effect

- The false consensus effect

- The availability heuristic

- Confirmation bias

- The observer expectancy effect

These biases lead product managers and product designers to create beautiful products that underperform or fail in the market place.

The Above Average Effect

The above average effect is cognitive bias, where a person overestimates their own qualities and abilities in comparison to others. They believe they’re better than average. They could be smarter, funnier, a better driver, a better product manager, or a better designer.

In business, this may be a good thing: it takes confidence to start a company. On the other hand, we can’t all be above average. By definition, fifty percent of us are below average in a given area, and all of us are below average at something. Your competitors may be better than you.

In the area of product management or design, it’s easy to overestimate your knowledge of the customer, the value they see in your product, and the simplicity of your design.

The False Consensus Effect

The false consensus effect is where people tend to overestimate the extent to which their opinions, beliefs, preferences, values, and habits are normal and typical of those of others. It leads to the perception of a consensus that doesn’t exist.

This bias is on display whenever you try to design a product for yourself, or you hear someone on the team say “if I was using the product”. If you build a product for yourself, you’re probably going to like it, but that doesn’t mean that your customers will feel the same way.

The Availability Heuristic

The availability heuristic is a mental shortcut, where we estimate the likelihood of something by looking at the number of similar instances that come to mind easily. If it’s easy to find examples, we’re more likely to believe in something.

This bias is on display when you speak to one or two customers who are very vocal about your product, and then assume that many of your customers feel the same way. It may also occur if you interview half a dozen customers, and then assume that they represent your entire customer base.

On a broader level, studies have shown that after reading an article in the media, people are more likely to believe that the premise of the article is true. If the premise of this article is repeated in other sources, this belief becomes even stronger.

Information like this is a starting point. It can help you understand who your customers are, identify potential product features, or identify potential problems. However, the data you collect from a small number of customers is not statistically significant. It may not reflect the broader customer base or their response to your product.

Moving from Bias to Evidence

There are a number of ways to reduce the impact of bias. It starts by accepting that you and the people around you are susceptible to bias.

In his book, Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman says there are two systems for thinking. System one is fast, effortless, and automatic. System two is the opposite: slow, deliberate, and effort full.

Here are some examples of thinking fast:

- 2 + 2 =

- Bread and

- Recognizing facial expressions

- Recognizing people

And here are some examples of thinking slow:

- 24 * 78

- Finding someone in a crowd

- Deciding where to go for lunch

- Finding your way in a foreign city

In order to reduce the occurrence of bias, we need to move from thinking fast to thinking slow.

In the product space, this can be achieved by developing a strategy for unbiased customer research, product ideation and validation; a process where we formulate and then test our ideas.

The ideas which emerge from personal vision, self reflection, and direct customer contact should be treated as a starting point. They represent things that can be done, but after that, you need to determine whether they should be done. Write them down, and then look for a way to test them rapidly.

You can find or test an idea using the following methods:

- Start with in-depth customer research. Interview or observe 5, 10, or 15 (potential) customers. This may sound like a lot of work, but you can reduce your effort by working in a team.

- Conduct a survey. This is a great way to move from data about 15 customers to data about 15,000 customers.

- Analyze your customer data, to determine how people have acted in the past. This can often be used to predict future customer behaviour and response to a feature.

- Run small, rapid experiments to see how customers behave when they are presented with new and different options in a product or marketing campaign.

These are just a few methods to test an idea, but don’t stop at one method. Combine them in creative ways to generate more evidence.

On the topic of evidence, it’s also important to consider the confirmation bias and the observer expectancy effect when looking for proof.

Confirmation Bias

The confirmation bias is a tendency to search for, interpret, favour, and recall information in a way that confirms one’s preexisting beliefs or hypotheses. People display this bias when they gather or remember information selectively, or when they interpret information in a biased way.

This bias is on display whenever you set out to prove something, without considering the alternatives. For instance, we often use Google to find evidence for an opinion. Google is very good at this. Unfortunately, it doesn’t tell you about alternate opinions, tell you how much evidence exists for each opinion, or tell you how good that evidence is.

There are a number of ways to reduce confirmation bias:

- If you believe that X is true, try to find proof that X is false.

- Change a yes no question into a multiple choice question. Should you do X, Y, or Z? This puts you in a better position to judge each option on individual merits.

- Consider the quantity and quality of the information for each side, and then reevaluate your position in light of the bigger data set. Your perspective may still be incomplete, but it will be much more balanced.

- If you want to show that something works, try to find areas where it fails. This is an important element of usability testing.

On the topic of usability testing, let’s look at the last cognitive bias.

The Observer Expectancy Effect

The observer expectancy effect is a form of reactivity, in which a researcher’s personal position causes them to subconsciously influence the participants in an experiment. This can lead to situations where the outcome of an experiment is skewed in one direction, leading to invalid results.

In the product design space, this effect may occur during a usability test when:

- The instructions you give refer directly to user interface elements

- You consciously or unconsciously nod or smile when a participant moves toward the right path in the user interface

- You answer the participants questions or confirm their opinion during the test

This kind of behaviour makes it easier for a participant to complete a task successfully, but it ignores the purpose of the test: to find errors, and make the design better.

Here are a few ways to reduce the experimenter expectancy effect:

- Ask the user to complete real world tasks, in terms that they would normally use. Don’t use system terms.

- Standardize everything in the test: the setup, the moderator script, the collection of the test results, etc. Then follow the same protocol in the same way for every participant.

- Present the tasks on cards for the participant to read aloud and refer to. Then get out of the way and let them get on with it, pass or fail.

- Create objective measures for success, in terms of completion rate and time taken.

- Invite other people to observe the test with you. Give them an observation sheet to fill in.

- Collate the results, identify the issues, and prioritize them together

In practice, this is easier said than done. It’s hard for a designer to let go of their work, but you can make it easier by asking someone else to help write, moderate and observe the tests.

In Conclusion

I’ve covered five cognitive biases. If you’d like to learn more, I suggest you look at the following course on EdX:

The Science of Everyday Thinking

It’s extremely interesting and informative.